- Home

- Steven Harper

The Havoc Machine Page 6

The Havoc Machine Read online

Page 6

“What about anyone from a nearby village? Is anyone else missing a child?”

More murmuring. “No, my lord,” said Vilma.

“Then we should go look for his parents,” Thad declared. “Ada. Farewell!”

And, ignoring their pleas to stay, he spurred Blackie ahead. Sofiya was left with no choice but to follow.

“I wonder how long it will take for this to evolve into a fairy tale,” Sofiya mused once they had cleared the village. “A variation of Hansel and Gretel, perhaps.”

“Or the Pied Piper,” Thad said.

“What?”

But Thad didn’t answer. Sofiya rode beside him, Dante gripped his shoulder, and the boy clung to his waist behind him. It felt strange to be surrounded by so many people after spending so many years alone. Even in the circus he held himself apart from the other performers. The sun had fully risen now, and he caught a hint of salt on the crisp air, though the Baltic Sea was many miles to the northwest. Now that he wasn’t actually in danger, the long night and his aches were catching up with him, and he fervently wished there were some way around the long ride back to Vilnius.

“Your horse is amazing, lady,” said the boy after a while. “He’s very pretty and I like the way his mane stands up. Like a warrior. What is his name?”

“It has none,” Sofiya said. “It is a machine.”

“Everyone has to have a name,” the boy said. He sounded upset. “Even a machine.”

“Perhaps you could give him a name.”

“Kalvis.”

“The blacksmith god of the Lithuanians,” Sofiya said. “Fitting.”

“Because he was made by a blacksmith,” the boy finished. “What’s your horse’s name, sir?”

“Uh…Blackie.”

“That’s dumb.”

“Now look—” Thad began.

“I’m hungry,” said the boy.

Feeling guilty, Thad pulled the loaf of rye bread from his coat. He should have realized. “Here.”

But the boy pushed it away. “Na, na. I can’t eat that. You have to give me something else.”

“There isn’t anything else,” Thad said, annoyed again. He pulled the vodka jug from his pocket. It sloshed. “Except this. But you’re bit young for—”

The boy snatched the jug from Thad’s startled hand, raised it to his mouth, and pulled his scarf down. Over his shoulder, Thad caught a glimpse of metal as the boy drank. Thad was off the horse so fast, Dante nearly lost his balance.

“Applesauce,” he squawked with indignation.

“What the hell?” Thad demanded.

The boy clutched the empty jug to his chest. The scarf that covered his face and hair slipped, revealing brass. Thad reached up and yanked the cloth away.

The boy was an automaton. The lower part of his face was metallic, with a square jaw that fitted neatly against a brass upper lip. A brass hinge was fitted neatly under a rubbery ear. The boy’s nose was a smooth bump complete with nostrils, though it was made of copper and didn’t match the rest of him. The upper half of his face was made of some flexible material. Rubber, perhaps. Eyelids blinked with quiet clicking sounds, and they even had tiny eyelashes. His eyes were wide and brown, but not glassy. Were they rubber as well? The boy’s forehead and the area around his eyes moved with easy fluidity and realism. In fact, the boy’s entire body moved with none of the stiffness Thad associated with other automatons, and his voice sounded pure and human, without the usual mechanical monotony or odd echo. His short brown hair even had a silky sheen. It probably was silk. Thad stared in shock.

“Dear God,” he said.

“Bless my—” Dante’s words were cut off when Thad grabbed his beak.

“This explains much,” Sofiya said. “The boy remembers nothing because he no memories. He uses alcohol as fuel. Havoc experimented on living adults but this was his first—”

“Shut it,” Thad snapped. “Just shut it!”

“Why?” Sofiya’s voice was deceptively mild. “Did someone give you the right to hand me orders? Are you my good Polish husband now?”

Thad wanted to round on her, snarl at her, but kept himself under control. Sofiya was a woman, and telling her to shut up was already a serious breach of etiquette, something his father would have bent him over one knee for when he was a child. And why was he worried about that now? He didn’t care what Sofiya thought. He made himself look up at Blackie and the thing in the saddle.

A child. This automaton had fooled Thad into thinking it was a real child. He felt like he’d been kicked in the head and his stomach oozed nausea. His skin crawled. The boy was the product of a clockworker, and who knew what it might do? It had been riding behind him for miles now.

“Thank you for taking me out of there.”

But he was just a little boy. And he sounded like—

“No,” Thad whispered.

“This boy is a masterpiece,” Sofiya went on. “So lifelike. I am impressed. Havoc was much better than I imagined.”

“Get off my horse,” Thad said to the boy. “Now.”

The boy shrank down inside the rags. “Are you going to hurt me?” he—it—asked in a tiny voice.

Thad was shaking. This…thing was the product of a murderous lunatic, the same sort of lunatic who had tortured his son to death. Thad didn’t rescue such monstrosities; he destroyed them. This abomination should be melted down.

But when he looked at those eyes and at the way he—it, Thad reminded himself fiercely—the way it huddled on the horse, frightened and alone…

It’s not frightened, Thad snarled inwardly. It’s only mimicking fright because its memory wheels are pulling wires and pushing pistons.

A sword threatened to divide Thad down the middle and he didn’t dare move in case it cut him.

I love you, Daddy.

“What are you going to do?” Sofiya asked. “Are you going to hurt him?”

Hurt him.

The sword shifted imperceptibly, changing his balance like the weight of the vodka bottle pulling him back from the pit.

“I’ll have to decide later,” Thad said in a stony voice. “Get off my horse. You can ride with Miss Ekk back to Vilnius.”

“Ha!” said Sofiya with a snort. “You rescued him. He rides with you.” And she turned her brass horse toward the road to make it clear there was no arguing.

Thad set his jaw, then mounted Blackie ahead of the boy, who still cringed away. “Put your scarf back on, boy.”

Blackie was tired, and the ride back went slower. No one spoke. Sofiya’s face remained pale. The boy held onto the back of the saddle instead of Thad’s waist, and Thad tried to pretend he wasn’t there. When they reached the outskirts of Vilnius, Thad started to turn toward the circus, but Sofiya pulled up short.

“No,” she said. “We must see our employer and explain to him what happened, though I am sure he already knows.”

“He does?” Thad raised an eyebrow. “Then perhaps we should take a nice stroll by the river together first.”

“Sounds wonderful.”

“Or get some breakfast.”

“Equally appealing.”

“But we won’t.”

“No.”

“Because?”

“We are dancing, Mr. Sharpe. He is waiting for us to come and tell him, even though he knows the truth, because he is waiting to see how much truth we tell him. And we must pretend he doesn’t know, and he will act as if he is unaware we are pretending he doesn’t know. Steps within steps, dances within dances, Mr. Sharpe. He likes it that way. In any case, I see no reason for me alone to bring him the bad news when it was your fault.”

“My fault?” Thad shot back. “I didn’t set off the explosive device that destroyed the castle.”

Sofiya shrugged. “Come dance with him, then. I am sure he will understand. In any case, Mr. Sharpe, you may be sure that he is watching, and he is expecting you. If you do not come now, he will send for you later and you will come anyway.”

&nb

sp; “Does he employ big men who break thumbs?” Thad touched the pistols at his side.

“No men. And he won’t hurt you, Mr. Sharpe.”

“Then why should I bother seeing him?”

Sofiya halted her horse in the middle of the road, much to the annoyance of the drover in the cart behind her. Thad halted as well. “How many people are in that circus of yours, Mr. Sharpe?”

“What? I don’t know. Sixty, maybe seventy.”

“Close friends?”

“Some closer than others.”

“He won’t hurt you, Mr. Sharpe,” Sofiya said, urging Kalvis forward. “Not if you come.”

“I see,” Thad said tightly.

“Applesauce,” Dante said as they rode into the city. The streets were already filled with morning traffic—horses with carts and women with baskets and men with bundles and children with books. Morning smells of bakery and manure and sewer slops and beer mingled together. Church bells pealed some distance away. Sofiya’s horse attracted glances, but not many—automatons were striking but not unusual.

“Does your parrot talk a lot?” the boy asked as they wove their way up the street.

“Too much,” Thad said. “And I don’t want to hear a great deal from you, either.”

“Bad boy, bad boy,” Dante muttered.

“Tsk!” Sofiya shook her head. “Such a dreadful thing to say to a child.”

“He isn’t a—”

“Ah! Here is the hotel.”

The hotel was wide and stolid, built to endure the steady Baltic winter. They left both horses in the stable next door. Thad was about to order the boy to stay there as well, but Sofiya took his—its—hand with an air of forced no-nonsense and led everyone inside past the desk man to a door on the second floor.

“Stay here,” she said, took a breath, and went into the room beyond. Thad felt guilty, as if he had sent her to take a punishment he himself deserved. Don’t be an idiot, he told himself, and waited in uneasy silence with the boy in the hallway. The floorboards were scuffed but clean, and glass-paned windows at either end of the corridor let in dim light.

“Have you killed a lot of clockworkers?” the boy asked.

“Yes,” Thad replied shortly.

“Is it hard?”

“Sometimes.”

“Do you like doing it?”

That question caught Thad off guard. “I don’t know,” he answered without thinking.

“Does it make you happy? Your job is supposed to make you happy.”

“Is it?”

“In a family, the mother stays home to help the children and keep house and the father goes off to work every day, whistling and happy because he likes what he does and he knows he is earning money,” the boy said, ticking off points on his rag-wrapped fingers. “And the children have lessons or an apprenticeship or they play.”

“Do they? And what about poor families, when the father takes whatever work he can, and the mother has to work too, and the children as well?”

“That is very sad,” the boy replied.

Thad stared. “What do you know about sad?”

“It was very sad when Mr. Havoc opened up my head and moved things around. It gave me headaches and made me scared.”

Thad felt his mouth harden into a line. “You are a machine. You can’t feel anything. You can only do and say what Havoc punched into your wheels.”

The boy didn’t respond. He only looked at Thad for a long moment with those enormous eyes, and Thad found he couldn’t meet them. He looked at the door instead.

“Doom,” Dante muttered.

“Shut it, bird.”

“Why do you keep your parrot when he’s broken?” the boy asked suddenly.

“He reminds me of someone I used to know.” Thad’s words were clipped.

“You should fix him. And you shouldn’t be so mean to him. He might leave.”

“He won’t leave. He’s a machine, and he does what he’s told.”

“Applesauce,” said Dante.

The door opened and Sofiya, still looking pale, gestured for them to enter. Thad obeyed with relief—facing this mysterious employer’s wrath felt suddenly preferable to standing alone with the boy.

The chilly room beyond contained a bed, table, and a set of ladder-back chairs. On the table sat a box with a grill on one side and a wire trailing from the back. Several dials and buttons made a row beneath the grill.

Because they weren’t moving, it took Thad a moment to see the spiders.

Dozens and dozens of the them clung to the walls and ceiling. They took up every available inch of space. They ranged in size from ant to dachshund. Some had winding keys sticking out of their backs. Brass and iron claws gleamed. Their eyes glowed blue and red and green, and they were all pointed at Thad.

Cold fear gripped Thad. He stood rooted to the spot a few steps into the room. The boy gasped and hid behind Thad. Even Dante fell silent. Thad couldn’t move, couldn’t think. The quiet menace of all those clawed machines was worse than an army of thugs.

Sofiya coughed hard and gestured at Thad to take a chair. He swallowed hard and forced himself to obey while Sofiya twisted the dials on the box. Thad’s mouth was dry. The boy huddled behind Thad’s chair, trying to stay out of sight. The box squawked, gave a burst of static, then hummed softly. The spiders didn’t move, though their eyes never left Thad. The half dozen weapons he carried felt tiny and childish.

“Mr. Sharpe?” The voice from the box was low and pleasant, almost grandfatherly. “Are you there?”

Thad had to try twice before he could answer. “I am,” he said.

“Good. The connection is excellent. Miss Ekk tells me you failed to do what I hired you to do. I am glad to hear the truth, but I’d like to hear your side of it, of course. We’re all friends here.”

“Are we?” Thad said. “Who am I speaking to?”

“Your employer, of course.” The voice was smooth as chocolate and carried no trace of an accent that Thad recognized. British was all he could make out, but he couldn’t pin down a region.

Thad worked his jaw. “Are you a clockworker?”

“I told you he is stubborn,” Sofiya put in.

“You were quite correct, Miss Ekk. Mr. Sharpe, like you, I take from clockworkers.”

“Take?”

“I take their livelihoods, you take their lives. Really, we’re quite the same. We both have large collections, for example. What do you think of mine?”

“It takes my breath away,” Thad said. “But you didn’t answer my question.”

A low laugh. “Indeed. I am beyond such classifications, Mr. Sharpe.”

“You are a clockworker, then. Only a clockworker talks that way.” The familiar anger and hatred tinged Thad’s world red.

“You’re rather like a bulldog, Mr. Sharpe. I think I rather like you.”

“Do you?” Thad said through gritted teeth. Right then, he wanted to smash the box and its stupid grill, even though he knew it would do nothing to the man who manipulated it. Already his mind was running in a hundred directions, looking for weaknesses, searching for ideas. But clockworkers were highly intelligent, and Thad’s main strategy for dealing with them was to catch them by surprise, when their intelligence was of little use. This clockworker had taken plenty of time to plan. Thad needed more information before he could act. Best to keep himself under control and see what he could learn.

“What is your name, please?” he said with forced politeness. “Since you do like me.”

“Yes.” A bit of static came over the grill. “You may call me…Mr. Griffin.”

“Pleased to meet you, sir,” Thad said. “I’d shake hands, but you seem to be out of sorts with that.”

“Miss Ekk tells me you brought a mechanical child out of Havoc’s workshop with you,” Mr. Griffin said. “Is it here?”

Thad found himself wanting to correct Mr. Griffin’s use of the word it. “Yes,” he said. “Can you say hello, boy?”

“H

-hello.”

The spiders swiveled at the sound of the boy’s voice and stared at him. He made a low sound and tried to huddle under Thad’s chair.

“Then I suppose the night wasn’t a total loss,” Mr. Griffin said. “Should Miss Ekk have the hotel send up something to eat? You must be hungry.”

Now that Mr. Griffin mentioned it, Thad became aware of a gnawing hunger inside him, despite the unease and the spiders. He was also was grubby and dirty from his crawl through the castle and the long ride. He thought of refusing on basic principle, then decided it would be idiotic—and rude—to turn down hospitality, and he didn’t want to be rude to Mr. Griffin right then. Food would also prolong the conversation.

“That would be nice, thank you,” he said.

“Miss Ekk, if you would be so kind? And while you are downstairs, please see to that other errand I mentioned earlier,” Mr. Griffin said from the box. Sofiya quickly exited, and Mr. Griffin’s chocolate voice took on an edge. “As for you, Mr. Sharpe, I would like to hear what happened and why you failed. In detail.”

So Thad told the story. He felt self-conscious talking to a box at first, and the spiders and his anger didn’t help, but it became easier after a while—he could pretend no one was listening but the boy. Through it all, the spiders remained motionless, and Thad relaxed somewhat. A maid brought the food—tea and bread and sausage and butter—and Thad continued speaking between mouthfuls. The boy, of course, had already drunk his fill of fuel some time ago.

When Thad finished, Mr. Griffin said, “I see. I can’t pretend I’m happy, Mr. Sharpe. I needed that machine badly, and you failed me. I had heard you were quite skilled, and it disappoints me to be wrong.”

It was meant to be a rebuke, but Thad didn’t much care what clockworker thought of him. Interestingly, this clockworker didn’t babble or go off on strange tangents like other clockworkers. He also stayed focused on what Thad was saying. Most clockworkers had short attention spans when it came to what other people were saying. Mr. Griffin had neither interrupted nor asked questions during Thad’s recitation. Very strange.

“Look,” he said, “I had no choice but to let the machine go if I wanted to save—”

The Importance of Being Kevin

The Importance of Being Kevin un/FAIR

un/FAIR The Havoc Machine

The Havoc Machine Iron Axe

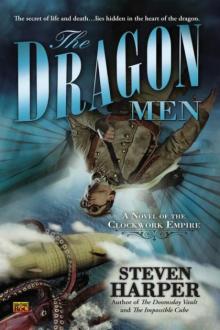

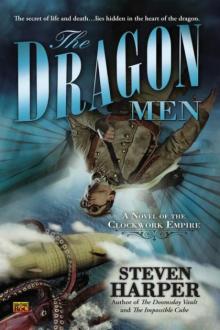

Iron Axe The Dragon Men

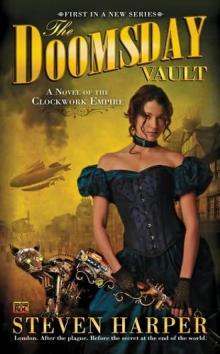

The Dragon Men The Doomsday Vault ce-1

The Doomsday Vault ce-1 The Doomsday Vault

The Doomsday Vault The Dragon Men ce-3

The Dragon Men ce-3 The Impossible Cube

The Impossible Cube Blood Storm: The Books of Blood and Iron

Blood Storm: The Books of Blood and Iron Trickster se-3

Trickster se-3 Offspring

Offspring Bone War

Bone War Trickster

Trickster Unity

Unity Dreamer

Dreamer The Havoc Machine ce-4

The Havoc Machine ce-4 Dreamer se-2

Dreamer se-2 Nightmare se-2

Nightmare se-2