- Home

- Steven Harper

The Havoc Machine Page 19

The Havoc Machine Read online

Page 19

Sofiya led Thad through the chaos to a pillar that held up the inside wall. “You didn’t see,” she explained quietly. “He chased after you when you ran with the bomb, and he failed to drop to the floor. The blast caught him.”

Thad’s feet crunched over broken glass and chunks of debris, and his stomach roiled with dread. Nikolai was sitting on the far side of the pillar with Sofiya’s dusty cloak bundled round him. At first, Thad couldn’t see anything wrong. His hair was mussed. The upper half of his face, the human half, looked perfectly fine, and the metal lower half showed nothing strange except dirt. But then Nikolai turned to look up at Thad. The other side of his skull had been peeled away, revealing thousands upon thousands of tiny wheels and gears. Sparks snapped and cracked across them.

“Th-th-thank y-you,” he stammered. “Th-thank you f-f-for taking m-me out-out-out-out of there. I-I-I don’t have-ave-ave one. M-M-Mr. Havoc-oc-oc called me boy-boy-boy-boy.”

Thad stared. “What’s wrong with him?”

“Something hit his head, where most of his memory wheels are stored,” Sofiya said. “It creates problems.”

“The victim-im-im of th-the cu-cu-cuckoo’s b-b-brood parasitism-ism-ism will f-f-f-feed and t-t-t-tend the baby-baby-baby cuckoo,” Nikolai sputtered, “even w-when the baby p-p-pushes the nat-nat-natural b-born offspring out and begin-in-ins to outg-g-g-grow the nest-est-est.”

Thad looked down at the automaton that fizzled and sparked at his feet, the worry he had been feeling drained out of him. He had been starting to think of Nikolai as more than he was, but now Thad could see he was still nothing but a machine. “Can you fix this?”

“Perhaps.” Sofiya’s face was stony again. “But nothing is certain. Perhaps we should talk about this elsewhere. That wall may come down, you know.”

Nikolai was unable to walk. Thad flung a fold of Sofiya’s cloak over his head and picked him up. “We can’t go far.”

“What? Why not?”

“The tsar and tsarina want to see us.” And he explained.

Sofiya’s eyes went wide, and she automatically tried to brush the dust from her clothes. “What of Nikolai?”

“We’ll have a servant put him a closet. No one will bother a broken automaton.” The words came out harsher than Thad had intended, but he didn’t back away from them.

“Thaddeus Sharpe!” Sofiya gasped. “That is—”

“Ser,” said a soldier. “If you and the lady will follow me, the tsar wishes to see you as soon as is convenient.”

It turned out “as soon as it is convenient” meant several detours. A small army of servants ushered Thad and Sofiya into bathing chambers, where they were scrubbed, perfumed, and dressed in smart new outfits. Sofiya’s cloak was whisked away for cleaning, and her ruined circus costume was exchanged for a rich green gown trimmed with gold ribbon and sporting utterly fashionable and thoroughly impractical pagoda sleeves. Thad’s new valet polished his brass hand and dressed him in a dark linen suit tucked into shiny boots under a long evening coat. Nikolai was not stuffed into a closet, but a footman was assigned the task of standing guard over him, to Sofiya’s evident relief. Sofiya gave Thad a number of dark looks, which Thad pointedly ignored. At last, Thad and Sofiya were escorted down the maze of corridors and hallways of the Winter Palace.

The palace was still in disarray. Servants scurried in all directions. People talked in hushed tones. Soldiers stomped about everywhere, often stopping hapless serving girls or boys to search them. Thad had no idea how much of it was military bluster and how much was part of General Parkarov’s investigation.

The phalanx of servants who had shepherded them through the baths took them to a heavily carved door and opened it. Thad forced himself to enter with firm steps and without gaping. Suddenly dealing with a mere bomb seemed easy. The opulent sitting room beyond had an enormous white fireplace. Shards of colored glass were inlaid in the chimney, and they threw sparkling scraps of light across the floor. The furniture was all white and gold, as were heavy carpets that seemed too fine to walk on. Every inch of the white ceiling and the baseboards had been done in gold scrollwork. Trays of food and bottles of wine occupied various end tables. An automaton played a balalaika softly in one corner. The tsar, also in a fresh uniform, sat in a wingback chair near the fireplace, and in the chair next to him was a small, delicate-looking woman with black hair and gray eyes—Tsarina Maria. Strands of pearls were woven through her elaborately braided hair, and the chair could barely contain the great yellow dress with its voluminous skirts and layer upon layer of crinoline. A dozen servants, male and female, waited in the background. Despite his awe at being twice in the same room with royalty in one day, Thad couldn’t help wondering how many peasants a single strand of the tsarina’s pearls would feed.

Sofiya is rubbing off on me, he thought as he bowed before both of them. Sofiya curtsied.

Tsarina Maria came to her feet and rustled across the floor to take both Thad’s hands in hers. They were small and cool, and her eyes were almost luminescent with emotion. “Thank you, thank you, thank you, Mr. Lawrenovich.” Her Russian carried a German accent. “I already lost one child years ago, and now you have prevented me from losing five more. I cannot thank you enough.”

“Majesty,” Thad replied, feeling more than a little overwhelmed. “I only did what any man would do.”

“No other man did,” Maria pointed out.

Thad coughed. “May I present Sofiya Ivanova Ekk?”

“Not his wife,” said the tsar.

“I’m sorry I missed your performance today, Miss Ekk,” the tsarina said, “though considering what happened, perhaps not extremely sorry. Come and sit. We will have cake and wine or perhaps tea.”

The servants seated them at chairs rather lower than the tsar’s and tsarina’s and set plates of food and drink at their elbows. Sofiya took her place with elegant grace, as if she had been dining with kings all her life. Thad nervously managed to take his own chair without stumbling, and he was careful not to use his brass hand for the wineglass, in case he spilled. Like the rest of the palace, the room was warm, almost stifling. Later, Thad learned it was because Tsarina Maria’s health was poor, and the entire Winter Palace was heated for her comfort.

“Now, then,” said the tsar with a gold cup of wine in his hand, “you must tell me from the beginning what happened and how you found the bomb.”

With a sidelong glance at Sofiya’s cool demeanor, Thad did so. It occurred to him that this would probably not be the last time he would tell this story.

“We must toast your bravery.” Alexander raised his glass. “To Thaddeus Sharpe Lawrenovich, without whom any of us would be sitting here right now.”

They drank. The wine was smooth and soft and perfect. Thad eyed the food tray—decorated cakes, pâté, cold chicken braised in wine, soft cheese, baked salmon, poached pear tartlets, pickled mushrooms, and caviar rolled into strips of sturgeon. He didn’t dare try a bite—his stomach alternated between tight tension and black nausea. The excess of wealth and power exuded by this room and its people made him uneasy and unhappy, and he wanted nothing more than to escape to familiar surroundings as soon as possible.

“You must be rewarded, Mr. Lawrenovich,” the tsarina said. From around her neck she removed a long strand of pearls strung with gold wire. “Accept this favor.”

It was on the tip of Thad’s tongue to refuse such a rich gift. But the circus man in him stepped up and snatched control. “Thank you, great lady,” he said, and slid the strand into his breast pocket. “It is too much.”

“Not compared to lives of my husband and my children,” she said with a sniff. “Now tell me, where did you get the little automaton? My children won’t stop talking about it. Did you build it yourself?”

“No,” Thad said quickly. “I took it—him—from a clockworker some time ago.”

“Yes! You are the famous clockwork killer,” Alexander said. “I have heard your name. How many clockworkers have you destroy

ed?”

Sofiya’s face remained perfectly impassive, and she fearlessly downed caviar and mushrooms. Thad flushed, then felt foolish for flushing. Why should he feel bad about slaying murderers like the one who had killed his son? The Tsar of Russia was praising him for it, for God’s sake. And yet the feeling remained.

“I don’t…keep track,” Thad said.

“It’s been that many, has it?” The tsar raised his glass again. “You do a great service to mankind. The tsarina and I would enjoy hearing of your exploits.”

“Do tell,” Sofiya said with patently false eagerness. “He won’t speak of it to me, ser.”

Thad saw the opening and exploited it. “It’s man’s talk,” he said. “Your Majesty might insist, of course, but such stories are…indelicate.”

“Why do you do it?” the tsarina asked before her husband could respond. “Clockworkers are dangerous. If they got hold of you, they could kill you. Or much worse.”

“It seemed necessary at the time,” Thad replied quietly. “Clockworkers are dangerous, yes, which means they endanger.” It was very hard to say these things with Sofiya in the room, true or not. Her eyes were perfectly calm, but he felt bad, hypocritical even.

“Clockworkers have their uses,” the tsar said. “They build fantastic machines. But they also bring filth into the world, as you have pointed out. Once we have wrung every bit of use out of them down in the Peter and Paul Fortress, we exterminate them.”

“We have seen,” Sofiya said mildly. “It was very instructive.”

What the hell was she doing? “I have heard,” Thad put in as a way to guide the subject in a new direction, “that the Chinese venerate clockworkers, call them Dragon Men and give them places of honor in their emperor’s court.”

The tsar made a disgusted sound. “Oriental barbarians. Not even the Cossacks would be so foolish. I assume you know what happened in Ukraine.”

“I do,” said Thad.

“That is what comes of letting clockworkers run around loose.” The vehemence in the tsar’s voice turned the air to bile. “They must be caged and controlled before they—”

“Now, now.” The tsarina patted his hand. “You mustn’t let yourself get worked up. You’ve already had a difficult day.”

“Yes, yes.” Alexander drained his cup and it was instantly refilled. “Difficult. Hm. You have a talent for understatement, my dear.”

“If I may, ser,” Sofiya spoke up. “Is it true that you have been thinking of emancipating the serfs?”

He eyed her over the rim of his cup. “These words have reached the streets, have they?”

“Rumors and speculation,” Sofiya said. “I know the landowners largely oppose the idea, and I myself wonder why such a wise man as the tsar would—”

“Huh!” Alexander snapped his cup down. “The landowners. They want to keep Russia in the dark ages. We are trapped with feudal ideas in a feudal economy. No other empire uses serfs in this day and age. Men must own their own land. Ownership creates pride and foments new ideas. Like Peter the Great before me, I traveled widely in my youth, and I have seen what new ideas can accomplish—navies and railroads and telegraphy and airships and electric power. None of these things were invented in Russia. Our people are stifled, and it’s to the good of the country that they are granted the freedom to do as they wish.”

This was clearly an old argument, but it had steered the conversation away from clockworkers. Thad shot Sofiya a grateful look, which she now ignored.

“So the rumors are true?” Sofiya asked pleasantly.

“You are too blunt for court, my dear,” the tsar said. “Your attempts to tweak information out of me are blatant. But everyone already knows. My legal scholars are drawing up the ukaz as we speak. When the new law is finished and signed—probably sometime in January—the serfs will be freed of their obligations to the landowners. Except for taxes, of course. No empire can run without taxes.”

“Is it possible, then,” Sofiya continued, “that the person who planted the bomb was a landowner who doesn’t want you to accomplish this feat?”

Alexander stroked his chin. “The thought had occurred. Do you have information about it?”

“Only speculation. It is why I—”

The door burst open, and General Parkarov dashed into the room with a box in his hands. He gave a perfunctory bow before the sovereigns. “Your Majesties. I have news of the investigation.”

The tsar half came to his feet. “What did you find, General?”

“These.” From the box he extracted two spiders, or what was left of them. They had been blown to pieces. He laid them on a table. Thad recognized them as ones that belonged to Mr. Griffin. His skin went cold despite the heat of the room.

“We found these bits in the Nicholas Hall.” he said. “Two working spiders escaped us. They are not ones employed by the Winter Palace.”

“Did they plant the bomb?” Alexander asked.

“I am certain.” The general’s eyes glittered as he spoke. “I inspected the throne room myself before you entered, and there was no bomb. No one approached the throne after my inspection, so it must have been these spiders who planted it, sent by a rogue clockworker. We must find him before he strikes again.”

“This is not necessarily—” Sofiya began.

“Do that,” Alexander ordered. “Whatever it takes. Send your men. Search the city. Bring him—or her—in.”

“Majesty.” Parkarov bowed and withdrew.

Sofiya looked like she wanted to say more, but the tsarina said, “Disgusting! Horrifying that some monster out there wants to murder my children!”

This time the tsar patted her hand. “We’ll find him, my dear. And then we can watch the machines tear him to pieces, as he deserves.”

“Ser, I wonder if you’ve considered—” Sofiya began.

“Mr. Lawrenovich,” Maria interrupted, turning to Thad, “you’re an expert at hunting clockworkers down.”

Uh-oh. Thad could see where this was going. He flicked his eyes toward Sofiya, but she just shook her head helplessly. “I…yes,” he said, trying to think.

“Then join the men,” she said. “Use your skills. Find that clockworker for me. And kill him.”

* * *

The machine was enormous now, both physically and mentally. Its body had added so many memory wheels and creation devices that it could no longer move about. It squatted at the intersection of five tunnels, taking in more and more and more metal, whatever the spiders could bring. It controlled a great many spiders. They skittered about the tunnels and the city above, giving the machine a perfect picture of the place. Half a dozen spiders were stealing books from the engineering section at the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences and flipping through them at blinding speed, transmitting words and concepts to the machine, then leaving them about for the puzzled men in the library to reshelve. Already there was talk of hauntings and poltergeists, despite them being men of science. The Master did not mind as long as the machine and the spiders were not caught.

The machine sent tentacles of wire and pipe through the tunnels. This was one of the few places in Saint Petersburg that actually had tunnels, an attempt on behalf of the Academy at a sewer and cargo transportation. The high water table meant tunnels were difficult to dig and expensive to maintain, however, and the project had been abandoned. The machine had taken advantage of the train tracks already laid down to transport the materials it needed, especially metal and books.

Many of the books were written by people called clockworkers. These clockworkers were held in a prison in the Peter and Paul Fortress on yet another River Neva island of the sort Saint Petersburg seemed to be prone. Most of the books hadn’t been written so much as dictated, and some of them rambled rather a lot, though their insights into physics and engineering and clockwork technology were proving invaluable, and they allowed the machine to continue its improvements. The clockworkers seemed to interest the Master very much, though he seemed to es

pouse no interest whatsoever in the clockwork plague that spawned them. The machine noted both these facts without emotion and continued its research and its improvements.

By now, the main part of the machine occupied the entire rather large intersection of the five tunnels beneath the Academy, and it no longer resembled a spider with ten legs, but was instead a chaotic mass of pipes and gears and boilers and claws and wheels and belts and mechanical hands. A cabinet that resembled a small brass wardrobe stood prominent in the center of this mass. The doors stood tightly shut. Next to it, a twisted chute coiled to the ground. The machine chuffed and puffed, and from an aperture at the top of the chute emerged a spider, gleaming and new. It spiraled down the chute and clattered to the concrete floor of the tunnel. It stumbled about drunkenly, then righted itself and scampered about as if excited. It bobbed on its new legs and made a squeaking sound. The machine chuffed and puffed again, and a second spider spiraled down the chute to land near the first. It also staggered. The first spider recoiled for a moment, then scampered over to investigate. The second spider came fully upright and, like the first spider, bobbed up and down, exploring its legs. The first spider extended a leg to touch the second. Abruptly, the second leaped on the first and tore at it with all eight of its own legs. The first spider squeaked in dismay and tried to disentangle itself, but to no avail.

The machine extended two mechanical hands, plucked the two spiders apart, and held them wriggling at a distance from each other. The second continued its attempted attack on the first, and the first recoiled in the machine’s grip. Aggression. Interesting.

The Importance of Being Kevin

The Importance of Being Kevin un/FAIR

un/FAIR The Havoc Machine

The Havoc Machine Iron Axe

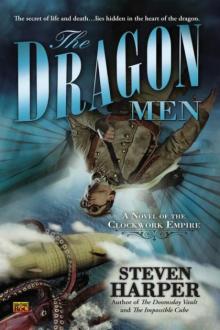

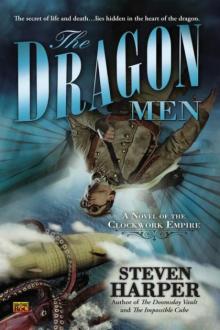

Iron Axe The Dragon Men

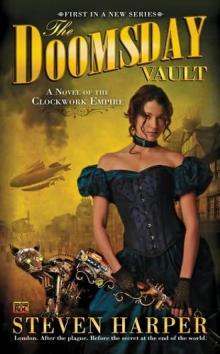

The Dragon Men The Doomsday Vault ce-1

The Doomsday Vault ce-1 The Doomsday Vault

The Doomsday Vault The Dragon Men ce-3

The Dragon Men ce-3 The Impossible Cube

The Impossible Cube Blood Storm: The Books of Blood and Iron

Blood Storm: The Books of Blood and Iron Trickster se-3

Trickster se-3 Offspring

Offspring Bone War

Bone War Trickster

Trickster Unity

Unity Dreamer

Dreamer The Havoc Machine ce-4

The Havoc Machine ce-4 Dreamer se-2

Dreamer se-2 Nightmare se-2

Nightmare se-2